Flying Blind: Gauging the Economy When Official Data Goes Dark

October 16, 2025

By Michael Madowitz

Fireside Stacks is a weekly newsletter from Roosevelt Forward about progressive politics, policy, and economics. We write on the latest with an eye toward the long game. We’re focused on building a new economy that centers economic security, shared prosperity, and rebalanced power.

Economic analysts often feel like pilots flying with dodgy instruments—but now the entire dashboard has gone dark. The government shutdown has frozen key reports on jobs, incomes, consumer spending, and more, with no plan to fill the missing data we should be collecting this week and beyond. For the second week in a row, the Fed, businesses, and households—and, yes, think tank economists—are flying without their most important gauges.

Beyond the data blackout, the broader economy was already hard to read. Job growth has slowed, manufacturing and construction are sagging, and many state economies are struggling.

Bottom line: We’re flying blind in a turbulent economy where dark clouds have been gathering for most of the year. In this week’s post, I detail why shutting down data collection in this economy is particularly foolhardy, how to think about alternative sources in the interim, and what we should demand from the government when this shutdown ends.

The State of the Economy: Uneven, Fragile, with a Weaker Inflation and Jobs Picture

The economy has clearly slowed this year, but enough odd crosscurrents make it hard to pinpoint what’s driving the slowdown—or how bad it is. Tariffs are pushing up inflation and slowing hiring, particularly in manufacturing, though not by enough to trigger a recession on their own (though this fluid situation seems to be changing by the day).

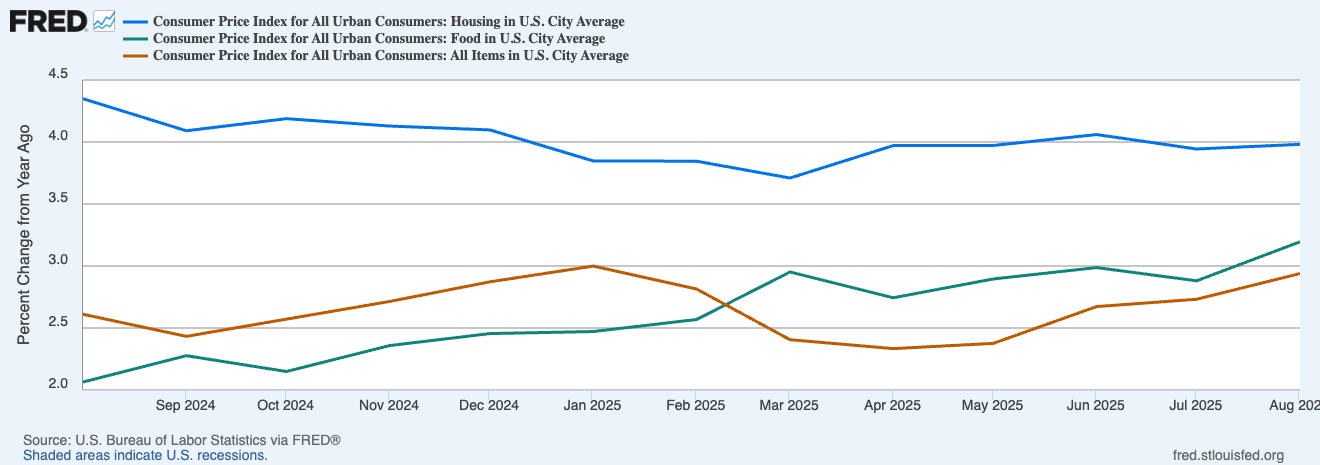

Rising costs are fueling anxiety for families and frustrating economists and policymakers who are seeing hard-won gains reverse. After declining for years, inflation was basically at the Fed’s 2 percent target a year ago. But this year it’s reversed, and has been creeping higher for months. Cheaper eggs and OPEC’s push for much lower gas prices (designed to crush US oil producers) have been outweighed by rising prices and slower wage growth elsewhere.

Housing and food inflation still outpace overall inflation, and utilities are up almost 8 percent year over year as of August. The long-running cost-of-living crisis in housing, education, and care persists, and policy changes are making things worse. For instance, health-care inflation—already above 4 percent—will likely rise further once the effects of the administration’s tax bill kick in this November, dramatically increasing health-care premiums for millions. And harsher immigration policy is throttling labor force growth.

The State of Economic Data: The Lights Are Out

With this much volatility, it’s precisely the wrong time to turn off the data tap. And it really is shut off, making the economy harder to read in addition to gumming up the work of straightforward governing.

For instance, aggressive shutdown plans have sent home entire statistical agencies, delaying key economic data releases and risking deeper disruption in the months to come. The shutdown reduced the entire Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)—the agency that produces inflation and job market data, among others—to a single employee. When it became clear that Wednesday’s missed consumer price index (CPI) report would jeopardize annual cost-of-living benefit increases for 71 million Social Security recipients, the White House recalled additional BLS employees to compile and release the previously collected September data, now planned for next week. This is a necessary step, but a skeleton crew of unpaid staff can only finalize the statistics thousands collect and process—that’s not a recipe for reliable statistics (and the field collection for next month’s data is already lost).

Private data firms—or at least their marketing departments—have sprung forward to offer assistance. What they can offer is limited. Virtually all useful private data exists as a branch of the broader federal data project (the trunk, which has been under-resourced for years). While this public data infrastructure may lack the novelty some private data have, that infrastructure remains the backbone of everything else we measure—including essentially all new and buzzy stats being pitched right now.

It’s not just that private data depends on federal data; it’s that no one—no matter how smart—can match the work of a capable state. Roughly five years on from a pandemic that set off the greatest surge of innovative economic data production in history, almost all of those projects—even those from the most impressive teams—were abandoned. With federal statistics offline, markets and experts are doing our best with what we have, yet there’s little effort to relaunch these projects—just a chorus begging for the best data we have to come back online.

Reading the Economy Without the Dashboard

The first rule of flying without instruments is…don’t! That’s good advice for policymakers too, and the rest of us should be especially wary of buzzy new statistics. Still, a few data sources that are still being compiled, or that don’t rely on federal statistics, can, in the right hands, provide limited information in the short term.

The Department of Energy’s weekly reports (and higher-frequency API) are still updating and provide one of the best commodity pictures of energy demand and prices in the US, a proxy for activity in the real economy and a public source that makes market data on many commodities informative.

Other data can still be useful, either telling us things federal data can’t or—at least historically—predicting or correlating with official data. The Baltic Dry Index proxies demand for goods shipping (it’s doing well this year, but obviously trade data are going through unusual times).

Auto sales—reported by manufacturers—are strongly correlated with consumption spending, partly because auto sales are sensitive to the economy (read: you don’t lose your job and buy a new car). Auto sales also make up a large fraction of total consumption spending. (Again, things are weird right now: Expiring electric vehicle tax credits boosted sales through September, but these data look solid.)

Yet, as the pandemic taught us, if analyzing alternative data feels like reading tea leaves, that instinct isn’t wrong. Caution is crucial. Still, there’s potential insight to be found in the noise.

Why the Data Must Be Restored

This data blackout, however, should be a wake-up call. Even under stress, federal economic data remain a crucial piece of our economic foundation and one of the last objective truths in America. Building on the legacy of statistics introduced to monitor the Great Depression and war mobilization, the US has the institutional knowledge and professionalism to expand and improve its open access federal statistics. For less than a cup of (pre-tariff) coffee, this world-leading state capacity gives a competitive edge to American small businesses, families, and taxpayers, who enjoy the lowest interest rates in the world due to trust built through years of independent statistical reporting.

We don’t need bespoke private data. We need to keep public servants in place, doing the hard work that keeps our economy running and makes effective policy possible. We didn’t give up federal statistics during World War II—if we had, we may well have lost! Protecting public data from the informational breakdown and factional politics that have infected too much of the public sphere is a crucial step in maintaining the civic infrastructure that allows a democratic society to choose political leaders who can deliver better economic outcomes.

An Open Call

We want to hear from you in these trying statistical times. What are your best recommendations for proxy stats to monitor the US economy in the interim? We’ll be asking our network of policymakers and economists over the weeks to come, but, much as it pains me to say it, there are no wrong (or right) answers right now.