Building the Government We Need: A Framework for Democratic State Capacity

June 6, 2024

By K. Sabeel Rahman

Introduction

In 2021, with the COVID-19 pandemic raging and the economy in free fall, Congress passed the American Rescue Plan, issuing billions of dollars of emergency economic relief. The bill included, among many other programs, directives for the Treasury Department to provide direct household economic support through a massive new Child Tax Credit. Under extraordinary pressure to stand up the program quickly, Treasury scrambled to build whole new divisions, computer systems, and capacities—engaging for the first time in the business of direct provision of benefits. Other agencies had similar experiences, scraping together new initiatives and exercising muscles that were either long-dormant or had previously not existed. But within a few months, another series of equally dramatic actions raised a very different specter, not of the bootstrapping of new government capacities, but of the active undermining of governmental authorities and initiatives. Through a series of major decisions, the Supreme Court undercut some of the very authorities and capacities agencies were building to address the COVID-19 crisis, stopping efforts to prevent evictions, protect workers from exposure, and forgive student debt.

This push and pull has continued to characterize many policy fights during the Biden administration. Empowered by additional new legislation and executive initiatives, agencies have begun a major revival of industrial policy and macroeconomic policymaking—investing billions in jump-starting new clean energy industries and physical infrastructure, while reviving antitrust policies to rein in new concentrations of corporate power. Yet many of those same actions have faced obstacles. Old procedures and fragmented institutions for permitting and building new projects have slowed the actual construction of infrastructure for which Congress initiated new funding. Meanwhile, new litigation has challenged the very foundations of legal authority for agencies like the Federal Trade Commission, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, or the National Labor Relations Board, undercutting the capacities those agencies have deployed to address inequities in the market economy.

"State capacity has to be actively built, dismantled, and reimagined in light of our overarching vision for a just, inclusive democracy and economy. As a democracy, we ultimately deserve a state with the capacity to empower, protect, and respond—rather than to exclude, dominate, and extract."

These flashpoints represent more than just tensions or disagreements over specific policies. They exemplify another underlying challenge for efforts to build a new, more inclusive and dynamic political economy in the years ahead: the need to build durable and effective state capacity. State capacity refers to the ability of the government to execute a set of policy priorities effectively (Linz 1978). Capacity is related to but distinct from performance—a state may possess capacities that are used poorly, or policies may be implemented that fail to generate the desired outcomes. But capacity also does not automatically result from the mere articulating of policy goals: It must be constructed and built.

This construction of state capacity—and state-building more generally—has been central to the history of progressive governance.

In the late 19th century, the pressures of industrialization, its impacts on communities and workers, and the rise of new forms of exploitative private control over essential infrastructure like railroads or necessities like milk drove reformers to develop new state-based regulatory agencies and public utilities. These agencies and utilities were charged with regulating industries to protect workers and consumers from harm and ensure public needs were being met (Novak 2022). The New Deal famously innovated a vast new federal bureaucracy that created the capacity to regulate markets and workplaces, and to deliver social security benefits, among many other programs. The Civil Rights Act created an enforcement apparatus to protect against various kinds of discrimination. The success or failure of the ultimate policy objectives for many of these programs required not only the setting of the legislative or regulatory goal but also the creation of bureaucratic institutions and structures capable of executing that goal.

Today, we see a revival of interest in this question of building and optimizing state capacity. With major new public investments underway in clean energy, infrastructure, and service delivery, a host of scholars and thinkers have warned that absent reform, existing state institutions may not have the capacity to deliver the desired outcomes effectively, quickly, or at sufficient scale.

This has been a growing concern in context of the need to rapidly build new clean energy infrastructure (Klein 2022), the push to address the accelerating dearth of plentiful and affordable housing by building more units more quickly (Demsas 2022), and the need to design safety net and service delivery programs that smoothly and painlessly provide benefits to those who need them most (Pahlka 2023). Across these accounts, a common theme is that the existing structure of the state may frustrate policy ambitions: Excessive procedures can unduly slow down government action; outdated requirements and mental models might create an excess of caution where more alacrity or creativity may be required; fragmentation of authorities across different agencies or between federal, state, or local bodies might further dissipate policy momentum.1 The very idea of industrial policy depends on and presupposes state capacity—on the ability of state actors to generate financing and tax revenues, which in turn can be channeled into investments in industries or safety net programs.2

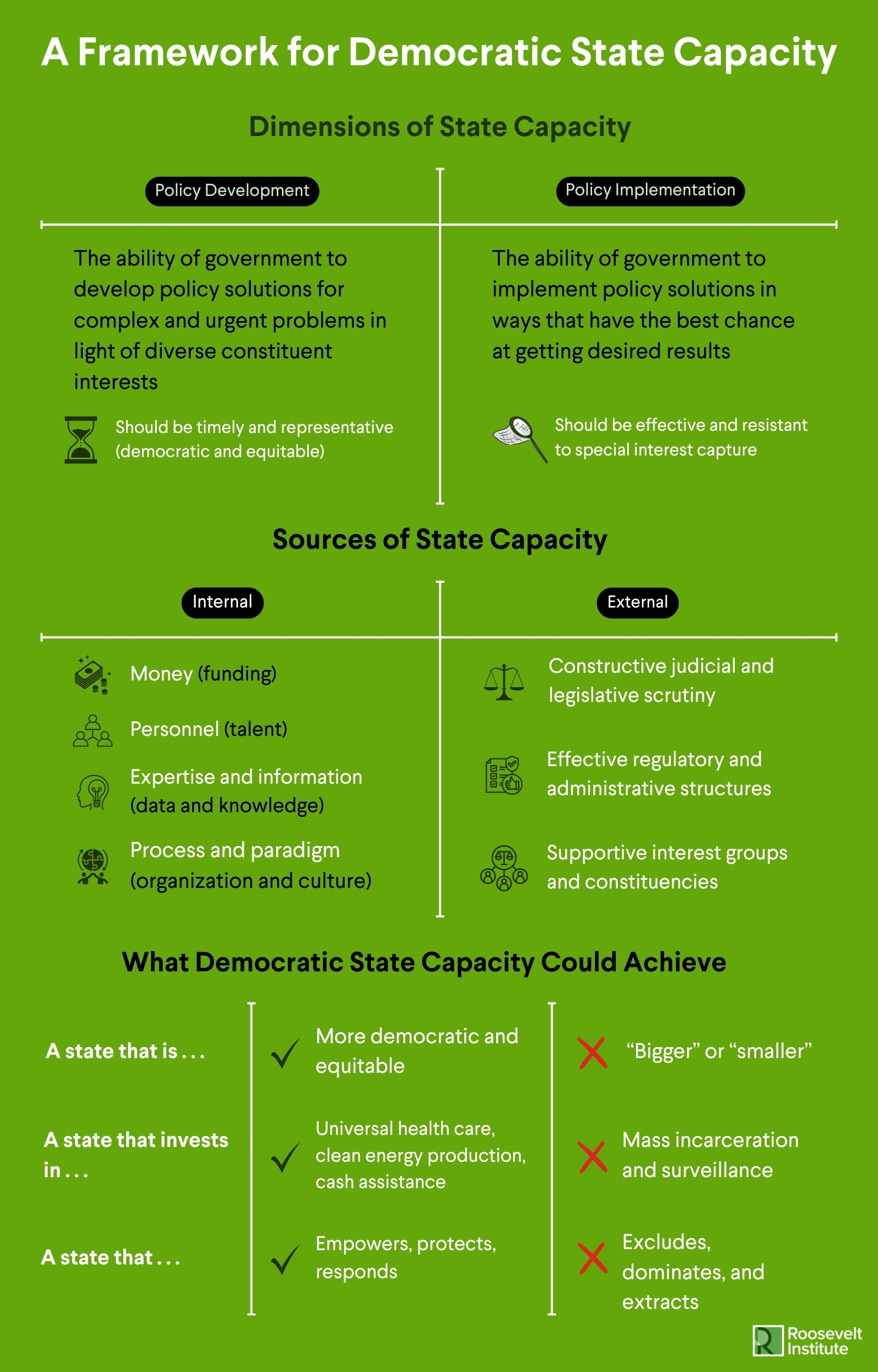

This report examines these questions of state capacity and the design of bureaucratic institutions to sketch a framework for identifying the various sources of state capacity or state incapacity. Conventionally, we might think of state capacity as a unidimensional, policy-neutral quality: States either have more or less capacity to effectuate whatever policy ends a government might set out to achieve. This, in turn, suggests a straightforward dialing up or down of constraints: More constraints mean less capacity; fewer constraints mean more capacity. However, this report seeks to broaden and nuance the discussion of state capacity to go beyond a unidimensional sense of “more” or “less,” and beyond the current focus on outdated or excessive bureaucratic protocols.

If our goal is to build an inclusive, sustainable, and dynamic political economy in the years ahead, we will need to reimagine how state institutions are structured and optimized.

First, this report suggests that state capacity must be understood not as a policy-neutral quality that dials up or down, but rather as a quality of governance that is intimately related to values of both democracy and equity. Understood this way, building state capacity in context of a broader agenda of developing a just, inclusive democracy and economy is about more than just removing outdated or excess constraints on state power. Rather, expanding state capacity will also require building whole new capacities that do not currently exist—for example, in service delivery, national planning, or the ability to address other structural demands for equity and inclusion. It will require dismantling some capacities that are implicitly or explicitly oppositional to the kinds of political economic goals we seek—not just at the micro level of outdated procedures, but also at the macro level of the ways in which larger state structures might enforce particular forms of racialized or gendered inequity—such as through immigration or carceral or punitive state structures.3

Second, this report also suggests that the task of building state capacity requires attention not only to the internal bureaucratic protocols and procedures that might limit state capacity; it also requires attention to a wider range of internal drivers of capacity, including resources, personnel, and information. Expanding state capacity will also require reconfiguring the external political economy around the state to address the ways in which external actors might deliberately sabotage or undercut the building of state capacities that might be needed, whether through political pressure or litigation.

Taken together, these arguments offer a conceptual framework for understanding state capacity—and ultimately for building the kind of state capacity we need to advance a vision of a just, inclusive, and democratic political economy.

Footnotes

Read the footnotes

1See e.g., Bagley 2021; Pahlka 2023.

2See e.g., Tucker et al. 2024.

3See e.g., Chertoff 2023; Shah 2023; Weaver and Prowse 2020

Suggested Citation

Rahman, K. Sabeel. 2024. Building the Government We Need: A Framework for Democratic State Capacity. New York: Roosevelt Institute.

Author

K. Sabeel Rahman

K. Sabeel Rahman is a Professor of Law at Cornell Law School, where his research focuses on the themes of democracy, economic inequality, exclusion, and power. From 2021 to 2023, he served in the Biden administration in the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs in the Office of Management and Budget as senior counselor and associate administrator (delegated the duties of the administrator).