The Cultural Contradictions of Neoliberalism: The Longing for an Alternative Order and the Future of Multiracial Democracy in an Age of Authoritarianism

April 18, 2024

By Shahrzad Shams, Deepak Bhargava, Harry W. Hanbury

Neoliberalism must be understood not only as a policy project but also—equally—as a cultural project.

Progressives must meet the widespread longing for alternatives on the terrain of culture if they are to compete successfully against the authoritarian vision of the post-neoliberal Right.

Executive Summary

Neoliberalism—the ideological, economic, and cultural paradigm that has reigned in the United States and around the world since the 1970s—is under siege. Progressives have offered a compelling alternative vision for how a post-neoliberal economy and government should work, and they have scored notable policy successes in recent years.

The post-neoliberal Right, by contrast, has focused less on policy and more on culture, promoting an alternative moral order and vision of the good life that has energized a mass movement and threatens multiracial democracy in the US.

In this report, we make five connected arguments. First, we argue that neoliberalism must be understood not only as a policy project but also—equally—as a cultural project. The key tenets of neoliberalism—the focus on the “rational,” self-interested individual as the fundamental unit of social analysis; the idea that free markets are a panacea; a preoccupation with personal responsibility and self-reliance; and the emphasis on an individual’s “freedom to choose”—have shaped and been supported by a range of cultural practices, beliefs, and worldviews. These include “grind culture,” the shaming of those viewed as having failed to succeed in the market, and the ubiquitous, individualistic life strategies, like self-improvement, that people have adopted to try to “make it,” or at least mitigate the risks of failure.

Second, we argue that we are living in a landscape of the cultural wreckage brought about by neoliberal policies and ideology. Mounting despair, mental health problems, overwork, addiction, loneliness and social isolation, and internalized shame are some of the profound negative social and psychological consequences of the neoliberal order.

Third, we argue that neoliberalism as a cultural project is increasingly unpersuasive and unsatisfying to many people. Neoliberalism’s failures have engendered a deep longing to meet needs not satisfied in neoliberal society, such as the need for community and belonging, for safety, for agency, for understanding, and for feeling good. To meet these needs, millions of people have developed and used various life strategies, some of which reconcile them to the neoliberal order, while others offer the promise of escape or alternative social arrangements. We focus on four archetypical cultural figures who have arisen in response to the failures of neoliberalism: 1) strivers, who commonly participate in wellness and self-help culture as a way of both adapting to and finding refuge from the harsh demands of neoliberal society; 2) innovators, who seek and create community-centered arrangements that satisfy desires for the kinds of social connection that are undermined by neoliberalism; 3) dropouts, who withdraw into private worlds, sometimes ones of private pleasures and sometimes ones of privatized despair; and 4) rebels, who solve for the failures of neoliberalism by participating in movements that challenge the established order, sometimes from the Left but more often from the Right.

Fourth, we argue that, compared to the Left, the Right has been far more strategic and successful in engaging with these four cultural responses to neoliberalism. This report focuses on a specific strategic avenue embraced by the Right in its mobilization efforts: its engagement with and weaponization of cultural responses to the failures of neoliberalism as a means for shaping worldviews, manufacturing consent, and recruiting individuals into its movements, all while speaking to people’s day-to-day concerns, lived experiences, and discontents. Diverse figures and movements such as Jordan Peterson, QAnon, JP Sears, and MAGA itself address certain needs not met by neoliberal culture while recruiting people to the far-right project. By adopting a “culture-first” orientation to politics, the post-neoliberal Right has used this cultural raw material as a vehicle for socializing its political vision. By contrast—and we believe less politically effectively—the Left has taken a narrower, more technocratic approach that focuses on policy agendas as a means of mobilization and recruitment.

Lastly, we argue that progressives must meet the widespread longing for alternatives on the terrain of culture if they are to compete successfully against the authoritarian vision of the post-neoliberal Right. Progressives must understand that longing to be the energetic taproot for any liberatory politics. This will require a dramatic renovation of organizing orthodoxies, progressive policy, and cultural habits on the Left. We find signposts for a path forward in the practices of past movements and today’s progressive organizations that are charting new ways forward.

Introduction

Nearly a century ago, Italian revolutionary and theorist Antonio Gramsci famously wrote from a fascist prison: “The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear” (Gramsci 1971).

Today, though far from dead, the old is slowly dying. Its grip is formidable, but neoliberalism—the political and economic order we’ve been living with for a half century—is embattled (Gerstle 2022; Wong 2020). As a policy project, neoliberalism is taking a beating from both left and right (Slobodian 2022). Less widely discussed, neoliberalism as a cultural project is also under enormous strain.

As historian Alex Zakaras (2022) has recently argued, the core myths of American individualism—the “independent proprietor,” the “rights bearer,” and the “self-made man”—date to the Jacksonian era. But in the neoliberal era, individualism reached a kind of ideological crescendo, expressed tartly by conservative UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher’s pronouncement that “there’s no such thing as society. There are individual men and women and there are families. And no government can do anything except through people, and people must look after themselves first” (Thatcher 1987).

Plenty of people still subscribe in whole or in part to neoliberalism’s core credo of individual effort in a meritocratic society leading to success, security, and happiness (Morgan and Steinbaum 2018; Sandel 2020). But increasing numbers of people are chafing against the “cruel optimism” (Berlant 2011) of the existing system. They see that following neoliberalism’s rules doesn’t produce well-being or a sense of security for most people—or even for many of the winners—because the system is rigged. And yet, individuals remain stuck in the old, desperately trying to cope with, escape, or transcend neoliberal paradigms with the same tools and life strategies that reinforce the ideology. The new cannot be born.

In the shadow of neoliberalism’s failures, a profound longing for an alternative order has taken hold across American society, expressing itself in a range of cultural counterreactions and adaptations to neoliberalism. In this report, we focus on four of these developments and the respective archetypical figures who tend to subscribe to them. Some of these developments, like the focus on self-care, the rise of mega fandom, and the surge in privatized entertainment, are ubiquitous. Others, like the opioid crisis, collective living, and sectarian strife in progressive organizations, are less so. These cultural counterreactions and adaptations to neoliberalism are embodied by a variety of cultural figures, some of whom are more conventional, like the entrepreneur obsessed with productivity and life hacking. Others are bizarre amalgamations of seemingly contradictory elements, like the QAnon Shaman or the supplement-popping, suburban yoga mom “red-pilled” into far-right conspiracy politics and vaccine denial (with the latter proving to have empirically notable consequences [Sun 2023]).

Strivers buy into the neoliberal worldview, at least in part—but they desperately need soothing to soften its rough edges, which show up in their lived experience as a lack of time, community connections, or meaning. They most commonly resort to wellness and self-help culture, turning the cultural tools of neoliberalism on the project of finding solace and working even harder to discover the right combination of products, classes, gurus, self-help books, or mantras that might soothe the ache at the center of their lives. The techniques strivers adopt often act either as a portal into political apathy by focusing their attention on themselves or, increasingly, as a channel into right-wing politics. This is because striving accommodates individuals to the neoliberal paradigm; it mainly functions as a way to remake the self in service of the broader neoliberal project—by making oneself more productive, more marketable, and more self-reliant. Yet striving can include some rebellious elements as well, particularly when it turns to soothing the hurt inflicted under the neoliberal order. While these rebellious elements are not the dominant characteristics of striving, they do sit alongside its more common, conformist dimensions, making for a contradictory mix of beliefs and practices that often end up being embraced by the same individual.

Innovators turn to community-centered arrangements to try to craft alternative ways of living—in collective living projects, new spiritual movements, support groups, cooperatives, mutual aid, or cult-like communities, both offline and online, that provide the substance or semblance of an alternative moral order. At their most extreme and under the command of a charismatic leader, community-centered arrangements can morph into abusive cults or organized pyramid schemes, like NXIVM or the Church of Scientology. But there are far more examples of alternative communities that are less extreme and not necessarily problematic. These arrangements are growing in number and hold different orientations to politics.

Dropouts tend to take a despair-driven response to the injuries of neoliberalism, seeing themselves or the system as failures and finding ways to numb or extinguish the pain—through abuse of substances (such as opioids, which provide the sense of connection and safety people understandably crave), or in extreme cases, suicide (the rate of which has grown by about 30 percent over the past two decades [Garnett, Curtain, and Stone 2022]). Dropping out also has less dramatic cultural expressions of withdrawing, such as declining labor force participation among some demographic groups (US Bureau of Labor Statistics 2023), abstaining from watching the news or keeping up with current events, and the explosion of privatized entertainment, from gaming to binge-watching.

Rebels find community through rebellious politics, most prominently in the peculiar combination of joy and rage that characterizes the MAGA movement. On the Left, for a far smaller group of people, the rise of sectarianism and intraorganizational strife is in its own way a morbid response to these times—turning rage at systemic failures against proximate targets who are thought to have betrayed the faith, and finding community among like-minded dissidents (Mitchell 2022). (Gramsci observed similar internecine left conflict in his times as the old order crumbled: In fact, he may have used the phrase “morbid symptoms” to refer to the ultra-left turn of the Italian Communist Party, rather than to the rise of fascism [Achcar 2022].)

These archetypes and the cultural responses they embody are useful in understanding the impulses arising as a response to the cultural crisis of neoliberalism—but they do not describe entirely separate groups of people or cultural developments. Most individuals carry DNA from each of these breeds, and most still believe to some degree in neoliberalism’s failed promise of happiness and success through individual effort alone (even if we ideologically disagree, our everyday practices usually, and often necessarily, affirm the ideology). Some progressives regard the odd or dangerous cultish beliefs held by millions of Americans with bemusement or contempt. But all of us are cultural Frankensteins, of necessity patching together disparate cultural resources to make sense of and forge a path through these tumultuous times.

While certain trends and movements must be challenged, it remains true that we need to approach the strange (sometimes morbid) subcultures that have emerged—and especially the people seeking meaning and solace in them—with curiosity. We cannot successfully engage with people whose inner lives we do not even try to understand.

At the root of much of the striving, innovating, dropping out, and rebelling is a simple and profound emotional impulse—a longing for an alternative way of being and living that is more satisfying.1 No matter the dysfunctional, strange, or antisocial nature of some of the specific responses, the longing itself must be understood as the energetic taproot for any liberatory politics and as a potential threat to the established order. The antidemocratic Right has harnessed this longing to fuel tribal, racist, and patriarchal politics—often organizing through avenues that meet people’s social and emotional needs, such as popular culture (Fisher 2021) and religion (Dias and Graham 2023; Dias 2023). The Left has, for the most part, focused its fire on the policy failures of neoliberalism and proposed credible alternatives in that realm, but has largely failed to engage with the deeper human needs and the cultural byproducts of the neoliberal project that the Right is increasingly tapping into.

It is critical, however, that progressives craft responses that speak more directly to the longing itself and are grounded in an alternative vision of the good life that can be lived, at least in part, in the here and now.

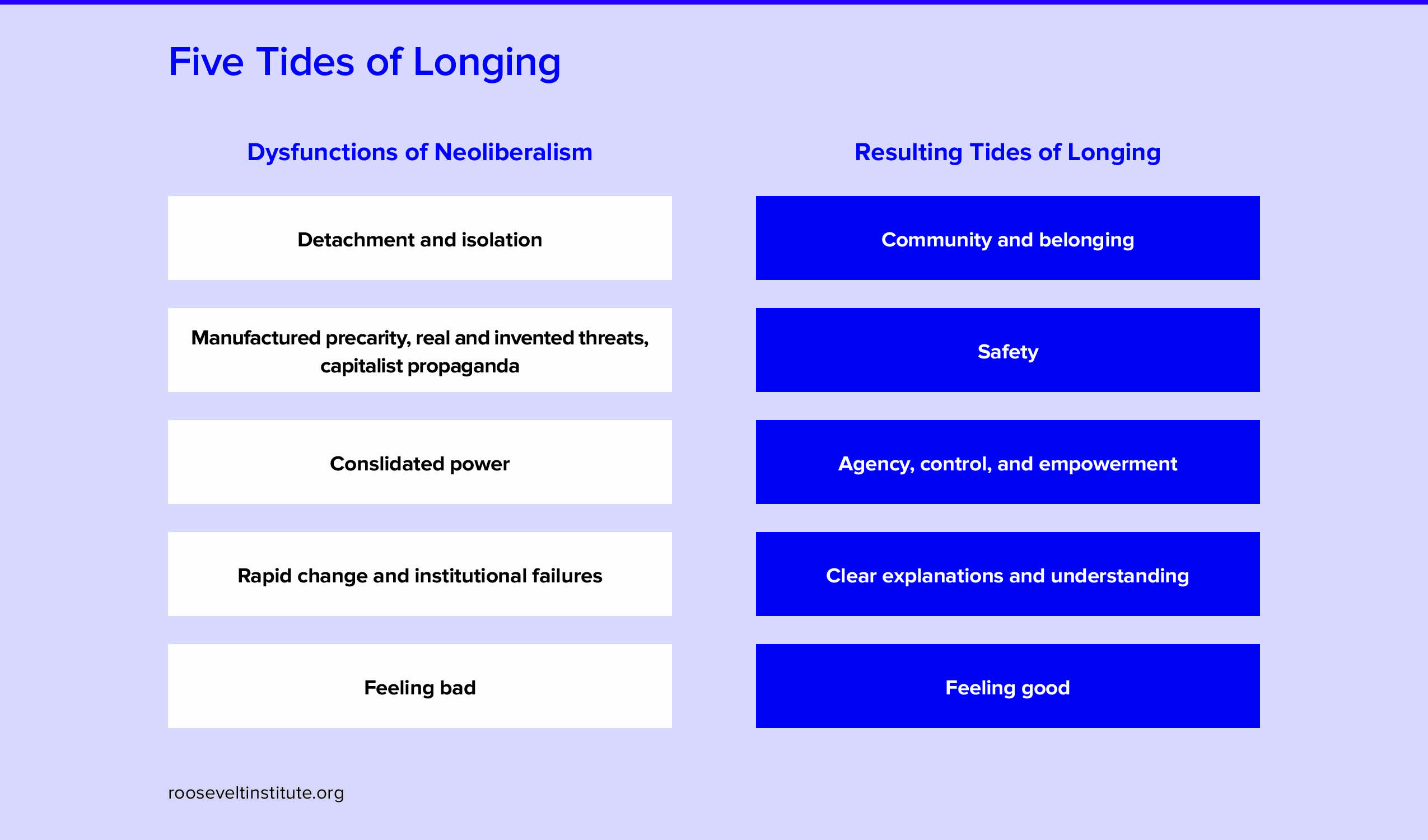

The cultural destruction inflicted by neoliberalism has five main characteristics, each producing a longing for its opposite. First, detachment and isolation have made us yearn for community and belonging. Second, manufactured precarity, real and invented threats, and capitalist propaganda have bred fear, insecurity, and a consequent desire for safety (the rise in gun ownership and the desire for “safe spaces” are paradoxically part of the same trend). Third, increasingly consolidated power at the upper echelons of our society and economy has produced real and perceived powerlessness over our conditions, and people crave a sense of empowerment, agency, and control over their lives. Fourth, rapid change and the obvious failure of major institutions in society have left us questioning how the world works and fostered a desire for understanding and clear, simple explanations. And fifth—perhaps above all—we yearn to simply feel good in a world that so often makes us feel bad.

Footnotes

Read the footnotes

1The desire for a more satisfying life is, of course, not unique to our present moment in time. But we believe that the acute mismatch—between this longing for an alternative way of being and the everyday reality of contemporary life—is what makes this moment in time relatively novel, and the need for a strong progressive response particularly urgent.