To Put Trickle-down Economics to Rest, We Need a New Tax Code

April 15, 2024

By Elizabeth Pancotti

Introduction

In 2017, former President Trump and congressional Republicans enacted sweeping changes to the tax code via the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). Many of the law’s provisions were not made permanent, however, and hallmark changes to the individual income and estate tax will expire at the end of 2025.1 As a result, a renewed debate over tax reform has kicked off among policymakers and will accelerate over the next year.

While the expiration of TCJA provisions creates an opportunity to revisit the tax code, today’s tax reform conversation need not, and should not, be confined to the boundaries of the TCJA’s provisions—with policymakers narrowly considering whether to return our tax code to its pre-2017 state or make current policy the permanent law of the land.

The path to the 2017 law was carved over more than four decades, under the false promise of trickle-down economics. As such, policymakers should view the tax debate as an opportunity to move the tax code beyond the failures of neoliberalism and cement an economic paradigm that rebuilds the middle class, rebalances power, and confronts racial and economic inequality.

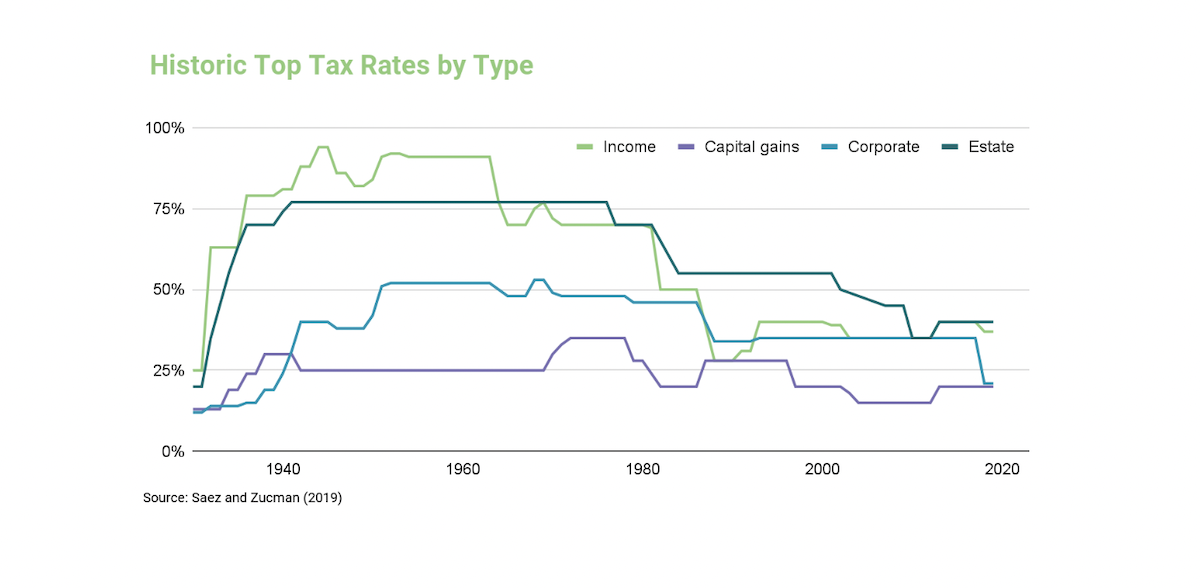

The Reagan administration’s embrace of supply-side economics underpinned its intense focus on tax reform (see Prasad 2019). Beginning with the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 (ERTA)—enacted less than seven months into his tenure—former President Reagan slashed taxes for individuals, especially at the top end of the income distribution, and corporations. As his argument went, these cuts for high-income Americans and corporations, and those that followed during his administration, would trickle down, creating jobs and spurring economic growth that would lift all boats.

Yet we’ve seen the opposite unfold. Since 1980, inequality has soared. Mid–20th century progress on narrowing racial wealth and wage gaps stalled, and in some cases reversed course. Concentration and consolidation of economic power has exploded. Tax revenue, as a share of GDP, has plummeted. Corporations have shifted away from investing in innovation and workers and toward maximizing returns to shareholders. Mounting evidence suggests that tax cuts for the wealthy make the rich richer and have little effect on economic growth or employment.2 Further, a growing body of literature finds that rising inequality constrains economic growth.3

Nevertheless, federal policymakers across the ideological spectrum continued to support and enact massive tax cuts for corporations and the wealthy during the some-40 years between the ERTA and the TCJA. Former President Clinton slashed the capital gains tax rate. Former President W. Bush lowered tax rates across the board for labor income, capital gains, and estates. Former President Obama made a majority of the W. Bush tax cuts permanent. Save for a few oscillations in various tax rates and bases since then, the trickle-down fallacy, despite mounting evidence against it, remains the bedrock of our tax code. While tax policy certainly isn’t to blame for every economic problem of the past four-and-a-half decades, it quarterbacked the neoliberal era.

Since assuming office, President Biden has hearkened back to an earlier era of tax policy, proposing tax increases primarily levied on wealthy individuals and corporations (Treasury Department 2021), though only two have been enacted. That approach is part of a broader shift away from neoliberalism in the Biden administration’s economic agenda, which has instead favored industrial policy, worker empowerment, and marketcrafting (see Tucker et al. 2023, Wong et al. 2024, and Hughes and Spiegler 2023). Biden has expanded the ambitions of his tax agenda throughout his first term, though many of his proposals are still anchored to the TCJA, simply adjusting rates between pre- and post-TCJA levels. His administration has said it supports extending some expiring TCJA provisions that, if allowed to sunset, would increase taxes for Americans making less than $400,000 per year (Condon 2024).

The jury is still out on whether the recent shift in policymaking toward a new economic paradigm will be short-lived or lasting. But given tax policy’s outsized role in the reign of neoliberalism, reforming the tax code is an essential component for its lasting demise. If policymakers narrowly focus on tinkering within the confines of the TCJA, we compromise the opportunity for enduring change.

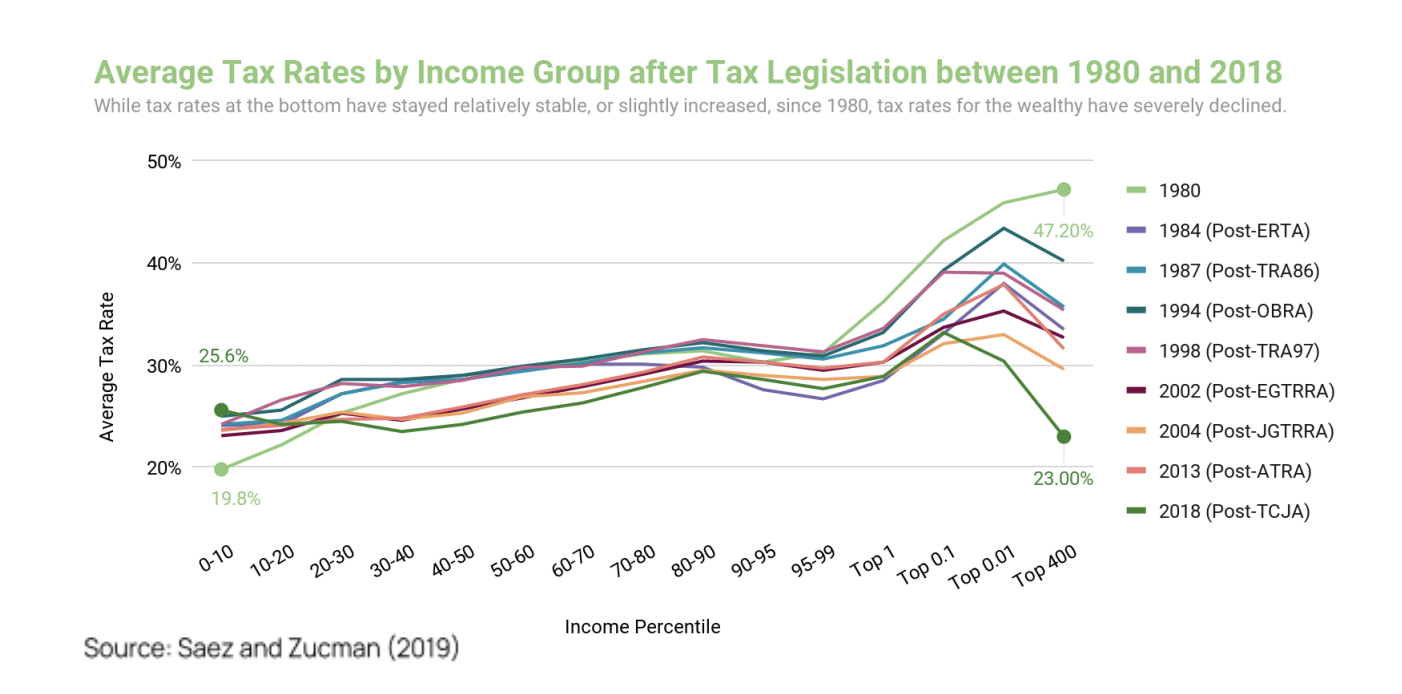

The Neoliberal Tax Code’s Path of Destruction

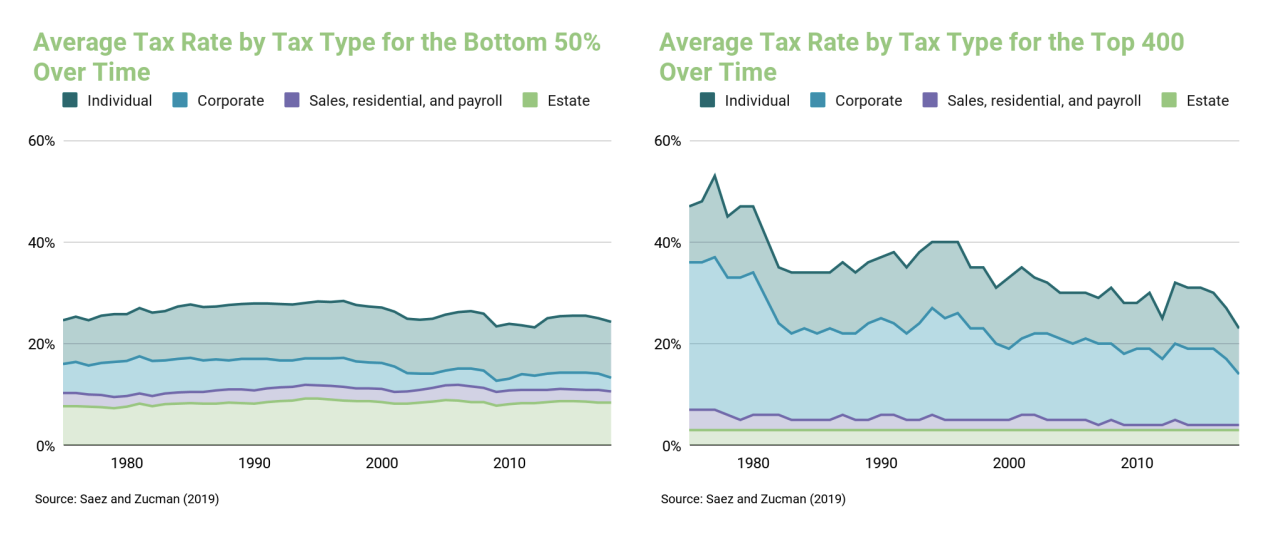

Between 1981 and 2017, trickle-down economics infiltrated the tax code through a series of tax cuts, heavily skewed toward corporations and the wealthy. The average tax rate for taxpayers in the top 0.1 percent fell from 42.2 percent in 1980 to 33.2 percent in 2018, compared to a reduction from 29.8 to 25.4 percent for median-income taxpayers and a slight increase from 22.2 to 24.2 percent for those in the bottom 10 percent. These cuts atrophied federal revenue streams. Following the ERTA, the share of revenue from corporate income taxes fell to a historic low in 1983 (6.2 percent), a reigning record until 2018, after the TCJA slashed the corporate tax rate by 40 percent (Tax Policy Center 2023c). Several significant cuts to the estate tax reduced the number of taxpayers subject to it from approximately 28,000 in 1982 to 2,600 in 2021 (Steele 2022). Beyond severe reductions in tax rates, there was a significant weakening in enforcement that led to a massive increase in tax avoidance.4

Despite mounting evidence after each law that the promise of job creation, wage increases, and economic growth failed to materialize, policymakers continued to enact further tax cuts—save for one brief experiment by the Clinton administration, described below. And far from trickling down, these tax cuts instead padded the pockets of wealthy shareholders, either by directly reducing their tax liability (e.g., capital gains and estate tax cuts) or incentivizing corporate behavior that benefited them (e.g., corporate profit and dividend tax rate cuts).

Footnotes

Read the footnotes

1For a description of expiring provisions, see Joint Committee on Taxation 2018a. Notably, the decrease in the corporate tax rate (from 35 percent to 21 percent) was made permanent. Conversely, tax cuts for middle-class families, such as the doubling of the standard exemption and the increase in the Child Tax Credit, were intentionally sunsetted to conform with Senate budget reconciliation rules that required them to offset revenue loss from the corporate tax cut. The primacy of corporate tax cuts relative to other TCJA reforms is illustrative of the chokehold neoliberalism has on the tax debate among policymakers in Washington.

2See, for example, Harris Bernstein 2016; Hope and Limberg 2020; Kindsgrab 2022; Zidar 2019; Piketty, Saez, and Stantcheva 2014; Furman 2020; Gale and Haldeman 2021; Howell 2013; Hungerford 2012; Tanden 2013; and Avi-Yonah, DiVito, and Lusiani 2024.

3See, for example, Bivens and Banerjee 2022; Bivens 2017; Alici, Kantenga, and Sole 2016; Stiglitz 2018; Furman and Stiglitz 1998; and Ostry, Berg, and Tsangarides 2014.

4 See, for example Dubin et al. 1990; Leviner 2009; Willis 1997; Gale and Krupkin 2019; and Schechter 2021.