The Myth That Shareholders Are Always Investors: Challenging the Paradigm of Shareholder Primacy

November 21, 2024

By Lenore Palladino, Harrison Karlewicz

Abstract

The assumption that shareholders buying and selling stock leads to real business investment is so deeply buried that it can be hard to see. The conflation of shareholding and investing—the concept that trading financial assets leads to productive investment in goods-and-services production—is not only conceptually confused but also perniciously supports the corporate governance paradigm of shareholder primacy. It is time to abandon the myth: Shareholders of corporations are not always, or even often, “investors.” Those of us holding financial assets intermediated by complex chains of financial institutions are not always contributing anything that improves production to companies. Calling financial institutions that manage pools of financial assets “institutional investors,” rather than “institutional shareholders,” perpetuates this conceptual error. Shareholding for purposes of capital appreciation does not necessarily lead to real economic investment. In fact, for publicly traded corporations, most real investment is not financed through the issuance or trading of shares. If firms finance the majority of their real investment through other means, we should not give shareholders exclusive power and special privileges in corporate governance.

"The conflation of shareholding and investing—the concept that trading financial assets leads to productive investment in goods-and-services production—is not only conceptually confused but also perniciously supports the corporate governance paradigm of shareholder primacy."

Introduction

“Corporations are controlled by their common stockholders. These stockholders are, in many corporations, not true investors; they ‘took a chance.’ Most corporations have at their financial base certain borrowed capital.” (Berle 1922, 1)

Among the many myths of mainstream economics is one so pervasive that it has crept into everyday speech: the idea that “shareholders” are always “investors.” The conflation of buying and selling financial assets with productive investment in goods-and-services production is not only conceptually confused but also perniciously justifies shareholder primacy: the idea that the purpose of all corporate production should be to financially benefit shareholders. It is time to abandon the myth: Shareholders of corporations are not always “investors.” This paper examines sources of funds that publicly traded companies use for real investment and describes how institutional shareholders engage with companies in the unregulated private financial markets. We argue that if firms with publicly traded equity finance the majority of their real investment through other means, and if private funds are engaging in extractive rather than productive behavior for their own financial gain rather than innovation and productive improvement, it is time to end shareholder primacy. An alternative explanation for the pervasiveness of shareholder primacy is that it perpetuates wealth inequality and thus is promoted with an interest in maintaining the status quo: Because the wealthy hold the majority of their wealth in financial assets, they have a strong interest in maintaining shareholder primacy.

Calling shareholders “investors” confuses real investment that companies do to innovate and improve their production process with the trading of securities on the financial markets and the purchase and sale of companies for financial asset appreciation (Lazonick 2018). Those of us holding financial assets intermediated by complex chains of financial institutions—through pools of funds that we refer to here as institutional shareholders—are not always contributing anything that improves production. Instead, we hold these assets to build our own wealth—usually, for the non-wealthy among us, for retirement. Retirement funds held $27.6 trillion in financial assets as of the end of 2023 (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2024). These are the funds that move from a person’s paycheck withdrawal or individual contribution into funds that hold portfolios of stocks, bonds, and other financial and real assets on both the open and private sides of financial markets. Most of us hope that, once we reach retirement age, the assets we parted with earlier in life will be worth enough in the financial markets to sustain our well-being. What happens to that money before we use it again is largely a mystery.

Retirement Security

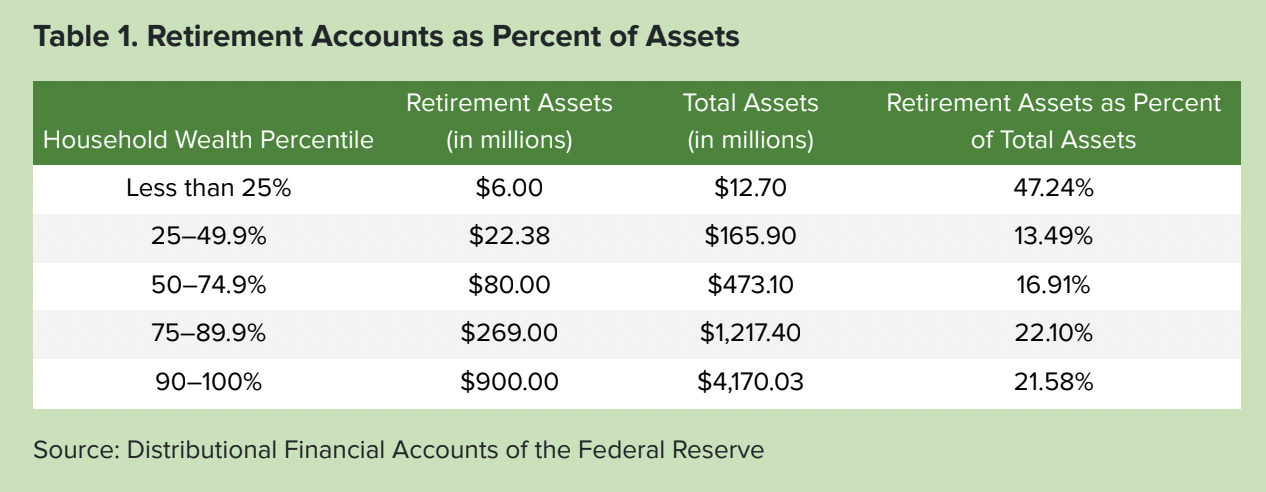

In the five decades since legal changes enabled pensions to purchase corporate stock, despite a ubiquitous cultural emphasis on the stock market as the key to retirement security, retirement security remains elusive. Economist Teresa Ghilarducci has shown that the retirement savings of an average US household fall short by $500,000 (Ghilarducci 2023). For non-wealthy households, retirement assets constitute a large portion of their net worth; though the dollar values are small, the lowest quarter of households by wealth percentile have the highest percentage of their total assets in their retirement accounts (see Table 1). Though an individual holding corporate stock in an employee or individual retirement plan does benefit as stock market values rise, the gains have historically not been sufficient to ensure financial security. A retirement system where individuals did not depend on an ever-rising stock market—and were not devastated if it happened to crash when they were about to reach retirement age—would be more secure across the income spectrum. Proposals to strengthen Social Security, create Guaranteed Retirement Accounts, and expand programs like the Thrift Savings Plan (the federal employees’ retirement plan) to all Americans would support retirement security much more sustainably than continuing to count on the stock market (Ghilarducci and Hassett 2021).

Colloquially, we call this process “investment,” which suggests that the money that you and I are saving turns into resources that are useful to goods-and-services–producing companies. When we transfer money from our checking account to a Vanguard Individual Retirement Account or to Robinhood, we call that transfer an “investment”: It is an investment in our own future, as we put our money in these funds in order to passively watch our wealth increase. However, leaders in the financial industry lead us to think that we are also investing in the future productivity of corporate America, even though our funds may simply be used to buy corporate stock that is already circulating on the secondary markets or to engage in many other types of purely financial activities. BlackRock CEO Larry Fink’s 2024 Annual Letter claims that “if more people could invest in the capital markets, it would create a virtuous economic cycle, fueling growth for companies and countries” (Fink 2024). By contrast, financial leaders such as John Bogle, founder of Vanguard, have spoken publicly about how the stock market actually works today:

In recent years, annual trading in stocks—necessarily creating, by reason of the transaction costs involved, negative value for traders—averaged some $33 trillion. But capital formation—that is, directing fresh investment capital to its highest and best uses, such as new businesses, new technology, medical breakthroughs, and modern plant and equipment for existing business—averaged some $250 billion. Put another way, speculation represented about 99.2 percent of the activities of our equity market system, with capital formation accounting for 0.8 percent. (Merriman 2016; italics added)

As Bogle explained, today the shares of publicly traded companies are traded largely on the secondary financial markets, and the money that we use to buy shares from share-sellers largely does not reach the company; it goes to the person or institution from whom we buy the shares. The only time money reaches the company is when they issue shares directly, whether through an initial public offering (IPO) or a secondary issuance. For the past two decades, companies on US stock markets have been repurchasing their own shares at a higher volume than they have been issuing new shares—which means that funds are flowing from companies to share-sellers, not the other way around (Palladino 2021a). Institutional economists such as William Lazonick have documented how much of the financing for improving productivity has come from retained earnings (Lazonick 2022). The confusion over the role of shareholders in the corporation is not new. Adolf Berle, author of The Modern Corporation and Private Property (often misread as arguing for shareholder primacy), pointed out that in the 1950s, 60 percent of real investment had come from retained earnings, while just 6 percent came from new equity issuances. As William Bratton and Michael Wachter explained in 2008,

Stock exchanges no longer served primarily as places for new investment and capital allocation, traditional functions only implicated in the rare instance of a new issue of common stock. The markets instead served as mechanisms for investor liquidity, a service provided for the benefit of the original owners’ passive grandchildren or the transferees of their transferees. The connection to capital gathering and productive allocation was for the most part psychological

Understanding the distinction between shareholding and investing is further complicated in the 2020s because the 20th-century division between “public” (in the sense of open to all) financial markets and “private” (open to only wealthy “accredited investors” and institutional shareholders) financial markets has broken down (Georgiev 2021; Palladino and Karlewicz 2024). Private1 markets are now the center of gravity in financial markets: Private funds have approximately tripled in size in the past decade to $26 trillion in gross assets (compared to the $23 trillion in the US commercial banking industry), and private markets raise more in equity than public markets (Gensler 2023; Ivashina and Lerner 2019). A common justification of the scale of shareholder payments made by publicly traded companies is that they enable “investors” to take funds out of the dinosaurs that still trade publicly and put those funds toward the young and hungry companies of the future, many of them not publicly traded in the private markets. However, much of the activity in private financial markets involves buying and selling for capital gains, without productive improvements (Ballou 2023; Christophers 2023). The data for sources and uses of funds is less available for private financial actors because they are under-regulated. But do we accept the myth just because we can see less of what is transpiring under the hood? This is not investment that furthers the productive capabilities of goods-and-services–producing companies—it is based on value extraction from non-financial companies. If we break the myth that shareholding and trading for purposes of capital gain is what enables businesses to thrive, it opens the aperture to rethinking the best structure for corporate governance and regulation of financial markets.

Buying Apple Shares Does Not Fund the Company’s Innovation

Apple is the world’s most valuable company by market capitalization and a key component of millions of portfolios, from household retirement accounts to multibillion-dollar institutional shareholders. Individuals and institutions purchasing Apple shares commonly believe that in doing so they are investing in the research and development and operations of the company. With these new proceeds, it is assumed, Apple is able to produce innovative products like the iPhones, MacBooks, and software many of us use daily. But the case of Apple illustrates that this common myth is mostly a fallacy.

In fact, Apple shares are purchased largely on a secondary market. The money that is used to buy shares from share-sellers might boost Apple’s share price, but it does not provide the company fresh capital. The proceeds go instead through a brokerage firm to the person or institution from whom

we buy the shares. Apple has not issued any new common stock since its IPO in 1980, which it used to raise a paltry $100 million (Lazonick, Mazzucato, and Tulum 2013; Koning Beals 2017). This means that the only Apple shareholders who contributed funds to the company to run its operations were those first purchasers of Apple shares in this IPO (Lazonick 2017a).

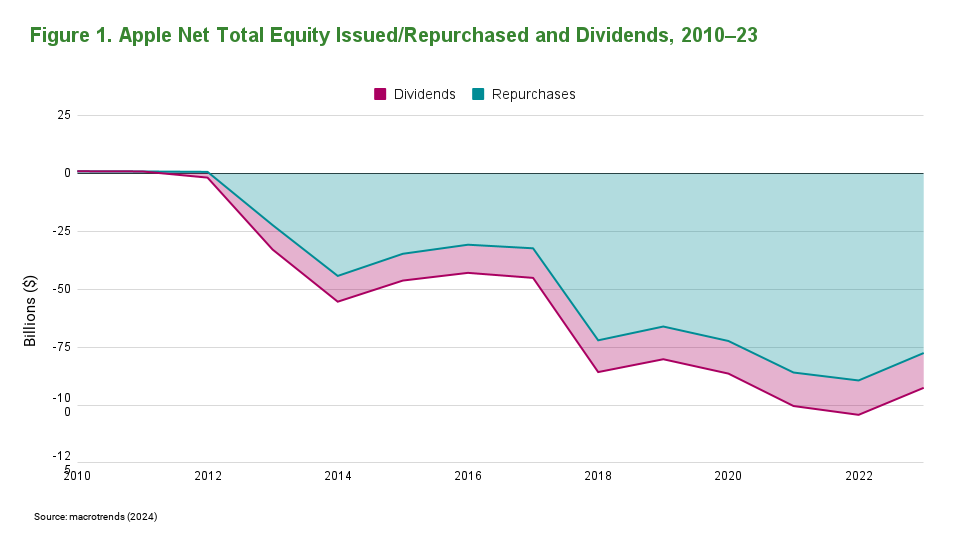

Rather than issuing new shares investors might buy to fund the company’s growth, Apple has been actively reducing its outstanding shares in recent years through repurchases. In May 2024, Apple announced plans to repurchase $110 billion of its own stock (Apple 2024), the largest share repurchase in US history (Kelly 2024). The size of the announced repurchase is a step up from previous years but maintains an ongoing trend for the company. Between 2023 and the start of Apple’s Capital Returns Program in 2012, the company spent $627 billion in net–equity repurchases and $146 billion in dividends (Figure 1). To put this spending in perspective, since 2013 the company has spent approximately $180 billion on R&D (Williams 2024) and seen its market capitalization rise from $500 billion to over $3 trillion (CompaniesMarketCap 2024).

As Lazonick notes, it is a misnomer on Apple’s part to construe stock buybacks as involving either “capital” or a “return” since the shareholders receiving cash through the Capital Returns Program are not in fact “investors” in any meaningful sense (Lazonick 2017a, 2018). In reality, the repurchase program is a transfer of cash to shareholders. This point is reinforced by the fact that at various points Apple has conducted repurchases at levels in excess of free cash flows, relying instead on reserves and borrowing to fund the program (Forbes 20212). Buying Apple shares, in sum, may boost the company’s stock and provide a financial return to shareholders. But trading these financial assets does not fund Apple’s innovation and production.

Public pension funds are of particular relevance as the dominant institutional shareholder in the United States. US public pension funds hold trillions of dollars of financial assets for the benefit of their current and future retirees. These pooled funds delegate authority to asset managers who then combine and organize these financial assets into new funds, which themselves purchase other financial or real assets, from stocks and bonds to whole companies. These types of asset owners are referred to as investors because in theory their assets are used to improve the actual productive capacity of non-financial companies. Yet the asset appreciation of the funds run by asset managers often is disconnected from a definition of investment that relates to the improvement of the production process, or innovation itself. Instead, asset appreciation is based on value extraction from non-financial companies.

In this paper, we first discuss how corporate investment relates to the stock market from several perspectives. Then, we present evidence on how corporate investment is actually financed for companies that trade their equity on the open markets and detail the attenuated relationship between shareholding for the purpose of asset appreciation and real corporate investment in the growing private markets. Finally, we explain why confronting the myth that shareholders are always investors is necessary to building a stronger, more innovative, and more productive economy.

If we break the myth that shareholding and trading for purposes of capital gain is what enables businesses to thrive, it opens the aperture to rethinking the best structure for corporate governance and regulation of financial markets.

Footnotes and Suggested Citation

read the footnotes

1This paper uses the terms open and public as synonyms, with private referring to the financial markets that are non-public, based on the traditional distinction in securities law.

2Free cash flow refers to cash flow left over after funds from operating cash flows have been allocated to capital expenditure and changes in net working capital. If positive, this remaining free cash flow is then equivalent to payments to creditors and shareholders (in the form of dividends and repurchases)—otherwise, if negative, it reflects additional net equity and debt financing. According to Compustat, Apple has generated significant free cash flows the past few years, such as $111.4 billion in 2022 and $99.6 billion in 2023. Apple also holds substantial sums of cash, although free cash flows were 2.3 and 1.6 times larger than these reserves in 2022–23. Since 2010, free cash flows have on average been 1.25 times larger than Apple’s holdings of cash and short-term investments.

Suggested Citation

Palladino, Lenore, and Harrison Karlewicz. 2024. “The Myth That Shareholders Are Always Investors: Challenging the Paradigm of Shareholder Primacy.” Roosevelt Institute, November 21, 2024.