Taking Stock of the New US Trade Agenda

October 23, 2024

By Todd N. Tucker

As the Biden administration enters its final months, the Roosevelt Institute and Roosevelt Forward have been looking back at the transformation of the American trade agenda over the past four years. Through a number of new pieces, we’ve examined how trade policy is being used to address challenges for labor and the climate crisis.

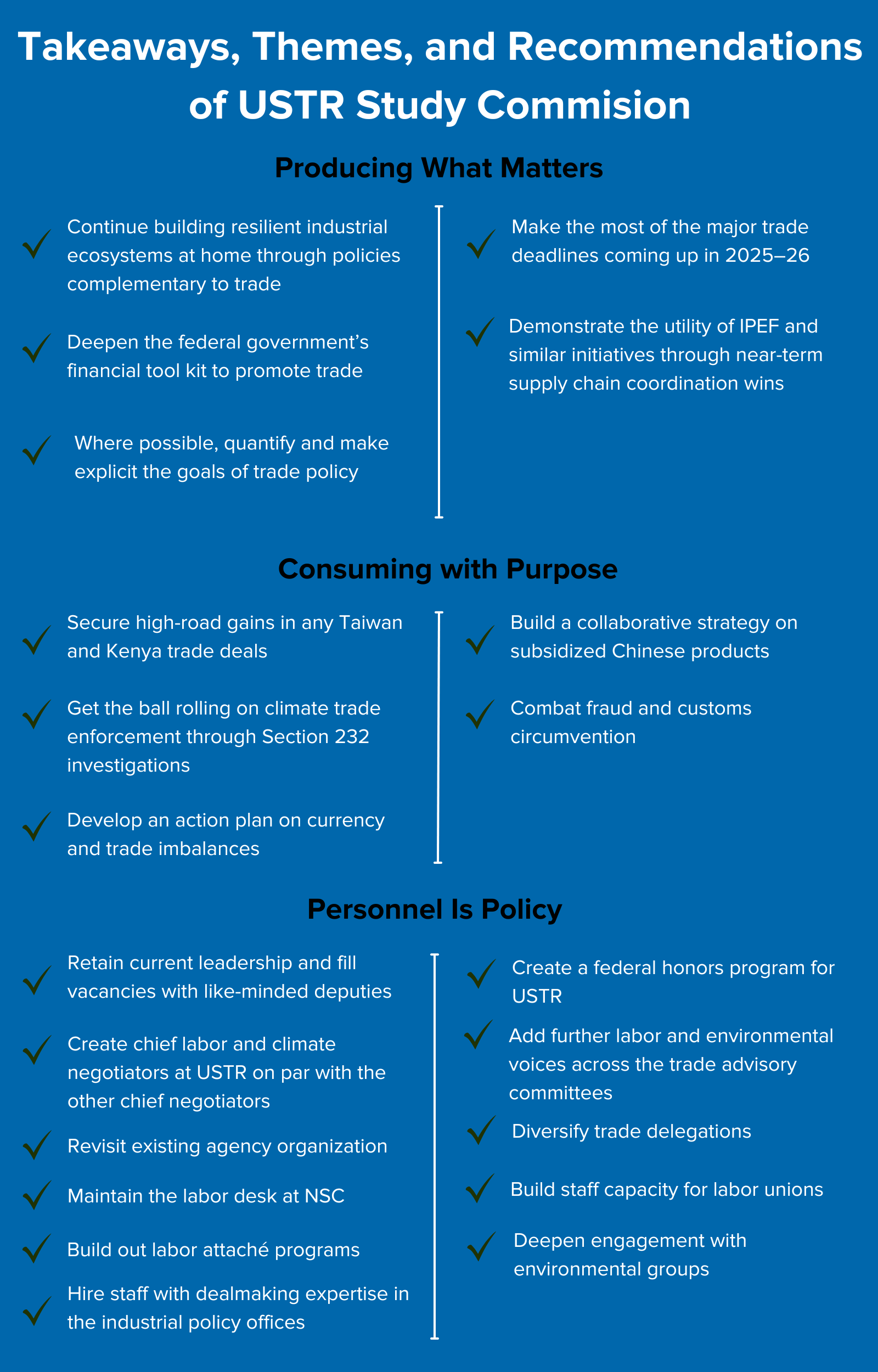

On Monday, the Roosevelt Institute released a report, The New US Trade Agenda: Institutionalizing Middle-Out Economics in Foreign Commercial Policy, that captures the findings of a 24-member study commission of scholars, former policymakers, and labor leaders organized by the Roosevelt Institute. Under the leadership of the Office of the US Trade Representative (USTR) under Ambassador Katherine Tai and through the efforts of the broader Biden-Harris administration, a new set of values has emerged, driving an ambitious economic agenda that includes reimagining how trade tools can further goals of resilient production and purposeful consumption. The report offers 21 recommendations for furthering this agenda in the next administration, ranging from urgent “inbox issues” like reauthorizing the Export-Import Bank to longer-range challenges like using trade to meet decarbonization targets. Financial Times editor and columnist Rana Foroohar highlighted the report in her Monday column, entitled “Power, as Well as Price, Matters in a Well-Run Economy.” We couldn’t agree more—our report argues for putting political economy and power analysis at the center of economic policymaking. (X thread on our report here.)

In a piece out today in Foreign Affairs, Ambassador Miriam Sapiro (former acting and deputy USTR during the Obama administration) and I go deep on one aspect of the new trade policy: the centering of workers and labor. In particular, we look at the nearly 30 cases brought by Tai’s team under the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement’s Rapid Response Labor Mechanism (RRM). This novel tool was added to Trump’s renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) at the insistence of congressional Democrats like Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-OH). It targets companies for remediation of labor violations rather than trading partner governments for failure to enforce labor law. The tool allows trade restrictions to be finely targeted at companies that abuse workers (rather than at US imports or the Mexican economy as a whole) and resolves disputes in a matter of weeks or months—rather than the years it took to resolve disputes in neoliberal-era trade deals. Thus, the RRM directly levels the playing field between US and Mexican workers while keeping the price tag for US consumers and taxpayers low. (X thread on the Foreign Affairs essay here.)

Last but not least, the fall issue of Democracy Journal features a debate between Roosevelt Forward’s Elizabeth Pancotti and myself, and blogger Matt Yglesias on the role that trade and tariffs can or should play in economic policy. As we’ve seen on the campaign trail, former President Trump is almost singularly focused on applying massive tariffs on imported goods. What exactly he hopes to achieve with this proposal changes by the day, ranging from forcing manufacturing back into the country to replacing the entire income tax system. Elizabeth and I argue that tariffs do have a place in a balanced industrial policy. But, they should be used as a scalpel to achieve specific strategic ends, protecting vital industries and interests—as the Biden-Harris administration has done with electric vehicles and proposed doing on green steel. (X thread on the Democracy Journal piece here.)

Zooming out, it’s clear that we’re in a very different place in the trade debate than we were just a few years ago. When the Roosevelt Institute published our first major trade report in the first year of the Trump administration, most Republican elected officials defaulted to supporting neoliberal trade priorities, and President Obama had recently gone on Jimmy Fallon to “slow-jam the news” and tout his proposed expansion of NAFTA through the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP). In 2024, despite (or perhaps encouraged by) the near-universal admonishment of economic experts, the Republican standard bearer Trump has doubled down on tariffs, calling it the “world’s most beautiful word.”

But the shift is much broader. Obama’s trade representative has written in Foreign Affairs that there is a “new Washington Consensus” on trade that includes tariffs; a recent Reuters poll showed a majority of registered voters supporting high tariffs; and key labor unions have argued that Trump hasn’t gone far enough on trade restrictions. Just today, National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan gave a second major speech to the Brookings Institution, arguing that distributional concerns need to be built into the fabric of trade policy, not treated as an afterthought.

Balancing the goals of protecting American workers and consumers while helping the world meet climate goals will be a central challenge for trade policy in the years ahead. Watch this space at Roosevelt Institute and Roosevelt Forward as we score the hits and misses, opportunities and challenges.