Supreme Corporate Tax Giveaway: Who Would Benefit from the Roberts Court Striking Down the Mandatory Repatriation Tax?

September 27, 2023

By Niko Lusiani, Matt Gardner, Spandan Marasini

“The findings in this brief open a window into the intertwined nature of economic and judicial power in the US today, and illustrate how tax policy by 'judicial say-so,' as Franklin D. Roosevelt once put it, would represent a deep challenge to American democracy in the 21st century.”

Executive Summary

Later this year, the Supreme Court will hear what could become the most important tax case in a century. In Moore v. US, ostensibly about the tax liability of an American family with minority shares in an Indian farming firm, the Roberts Court’s decision could stretch far beyond the plaintiffs themselves. The court could decide to place new limits on Congress’s authority to tax income under the 16th Amendment. While the court might take a narrow view based only on the facts and petitioners at hand, the court could also issue a broad decision that taxing income—of an individual or of a corporate shareholder—requires realization, and that income taxation on multiple years of accrued income is unconstitutional. If it makes such a broad ruling, the Roberts Court would suddenly supplant Congress as a major American tax policymaker, putting at legal jeopardy much of the architecture of laws that prevent corporations and individuals from avoiding taxes, and introducing great uncertainty about our democracy’s ability to tax large corporations and the most affluent.

New research presented here from the Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) and the Roosevelt Institute reveals how much specific corporations would save from a ruling by the Roberts Court striking down one particular provision at stake in Moore—the Mandatory Repatriation Tax (“MRT,” “repatriation tax,” or “transition tax”). We have identified almost 400 multinational corporations that would, if this tax is ruled unconstitutional for corporations, collectively be granted $271 billion in tax relief by the Roberts Court, according to these corporations’ own estimates. These are precisely the US multinational firms that have been willing and able to aggressively shift profits offshore for decades, and the amount of tax relief they would receive is the bulk of the $340 billion in revenue that the repatriation tax is projected to bring in. Amongst the biggest winners from annulment of the repatriation tax, Apple would be given $37 billion in tax relief, Microsoft $18 billion, Pfizer $15 billion, Johnson & Johnson $10 billion, and Google $10 billion. Just 20 companies account for over 60 percent of the tax savings identified here—all companies at the top of the Fortune 500. And this would hardly be a generalized tax break: The benefits from a high court ruling of this kind would be heavily concentrated in the pharmaceutical and tech sectors. Big Pharma would receive 23 percent of the total benefits, and Big Tech a hefty 45 percent of the total tax savings identified. In all, according to our estimates, 75 percent of the benefits of striking down the MRT would go to just three sectors: tech, pharmaceuticals, and finance.

In Moore, the Roberts Court could decide with the stroke of a pen to simultaneously forgive big business decades of tax dues in the billions; increase the federal deficit; jeopardize future public revenue and essential social programs; aggravate the disadvantages facing domestic, taxpaying competitors; escalate these multinational companies’ already sizeable after-tax profits; and further enrich their shareholders.

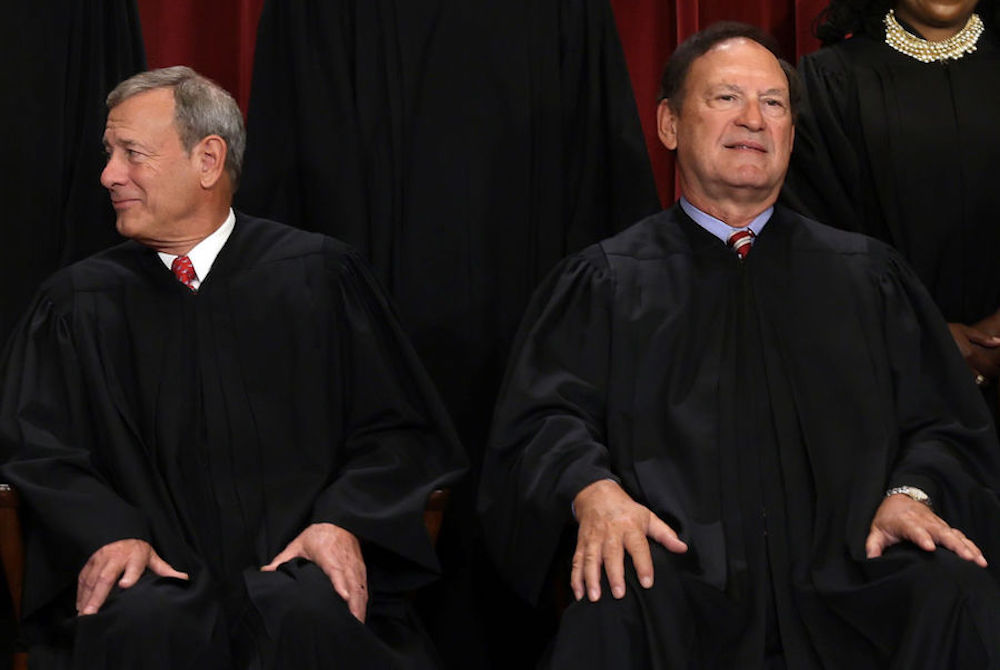

Two of the most notable of these shareholders are sitting on the Supreme Court itself. Here, we uncover that, according to their most recent financial disclosures, Chief Justice John Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito together hold stock in 19 companies set to receive over $30 billion in tax relief from a broad ruling striking down the repatriation tax for corporations. The fact that these justices might determine the outcome of a case that could grant a $30 billion tax windfall to precisely the companies in which they have direct ownership stakes presents a clear conflict of interest that puts into question the justices’ integrity and impartiality in Moore. More broadly, the findings in this brief open a window into the intertwined nature of economic and judicial power in the US today, and illustrate how tax policy by “judicial say-so,” as Franklin D. Roosevelt once put it, would represent a deep challenge to American democracy in the 21st century.