Abortion and Economic Policy, Part III: How Dobbs Rewrote the Economics of Reproductive Health, with a 275-Mile Price Tag

June 24, 2025

By Hannah Groch-Begley

Fireside Stacks is a weekly newsletter from Roosevelt Forward about progressive politics, policy, and economics. We write on the latest with an eye toward the long game. We’re focused on building a new economy that centers economic security, shared prosperity, and rebalanced power.

In this series for Fireside Stacks, Roosevelt’s Hannah Groch-Begley interviews experts who study the economics of reproductive rights. You can find previous entries in the series here and here.

Today marks the third anniversary of Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, one of the most consequential US Supreme Court decisions of all time. The decision was one of the few in the court’s history to entirely eliminate a right Americans had previously held for decades: the constitutional right to abortion. Following the court’s ruling, 13 states issued immediate, total bans on abortion in their jurisdictions, while 28 states introduced bans at different stages of gestation—Florida, Georgia, and Iowa all ban abortion after six weeks of gestation (before many people even know they are pregnant).

In our previous edition of this series on abortion and economics, we spoke with Middlebury College Professor of Economics Caitlin Myers on the experience during the Dobbs case of putting together a groundbreaking Supreme Court brief, which outlined what economists knew about legal abortion and how it influenced “the ability of women to participate equally” in economic life during the decades before 2022.

In the three years since Dobbs, much has changed. Professor Myers joined us again to discuss how she collects data on abortion and economics, and what that data shows us about the new normal for Americans seeking reproductive health care.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Hannah Groch-Begley: Thank you for joining us again! Let’s start with the headline question: Has the Dobbs decision stopped people from getting abortions who wanted to get abortions? Are more people giving birth because of the bans and restrictions on abortion access?

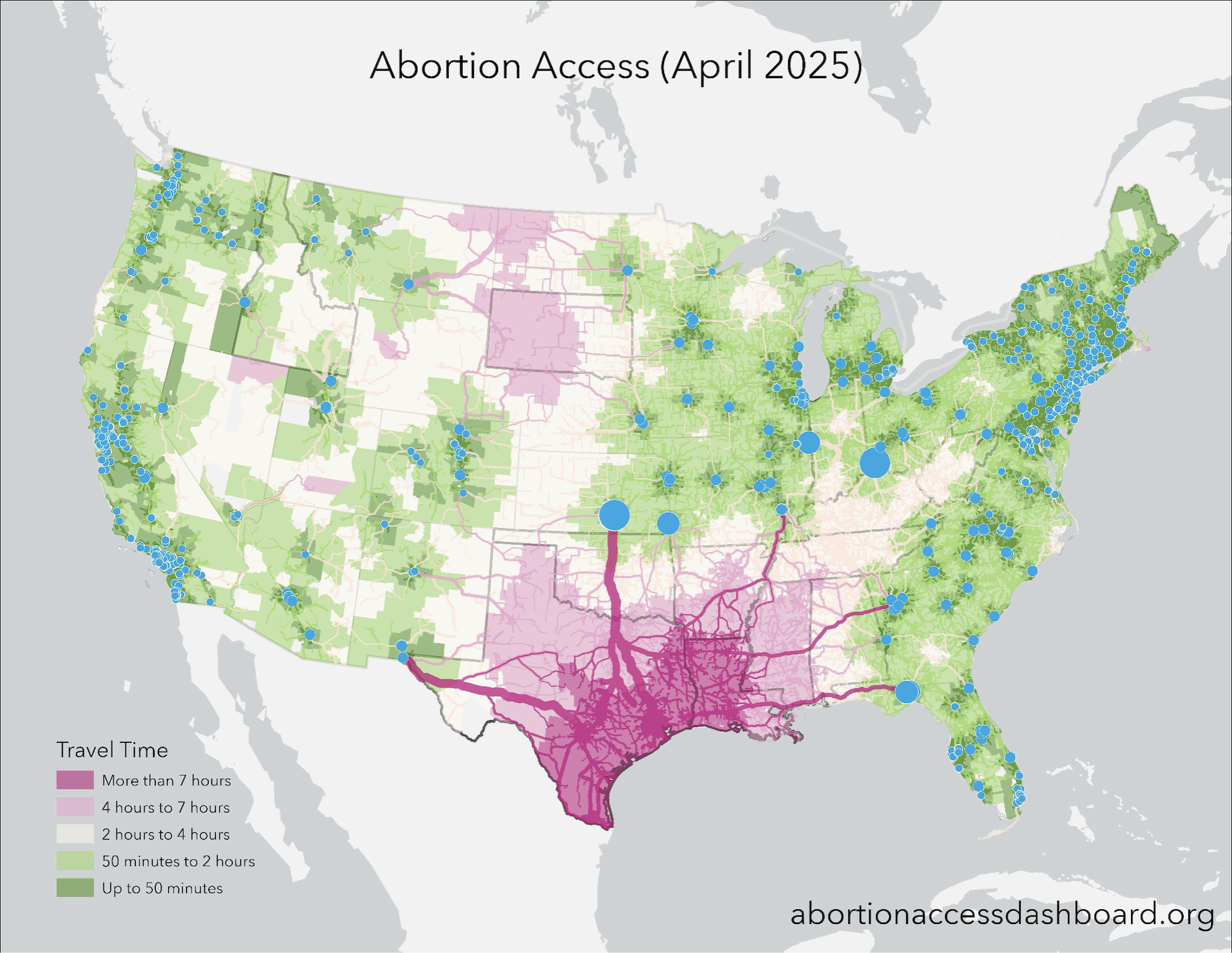

Caitlin Myers: Yes. The data we have so far shows that about a quarter of people in ban states who want abortions aren’t getting them any longer, and distance to a facility that offers abortion access is the single most salient factor that’s stopping them. The bans themselves, independent of distance, have a chilling effect, but it’s really distance. Births have gone up way more in Houston, Texas, than they have in El Paso, Texas, because El Paso is close to New Mexico. Texas has a total ban; New Mexico does not. El Paso residents can make appointments across the state border. So the new data shows very uneven impacts of Dobbs on births. The impacts are greatest in the counties where distance increased the most.

We see the biggest impacts for women of color, as is true in pretty much every paper in this field. We also see much larger impacts for women who don’t have college educations. We see much larger impacts on women who are not married than on women who are married. And so all of this, really compellingly, shows that the bans are stopping people who want abortions—not most people, but a significant minority. This significant minority are very likely to be among the most economically vulnerable families. Those are the families who don’t find a way.

Hannah: You’ve been studying this question of the effect of distance to providers for years, long before Dobbs. Can you tell our readers about the Myers Abortion Facility Database and why you created it?

Caitlin: I had been working on a series of papers on the effects of distance well before Dobbs was even on my radar. To do that work, I needed to gather information about where facilities were located and when they were in operation—when did they open, when did they close? And, essentially, what I discovered is that there really wasn’t a great source for the data that I needed. The Guttmacher Institute had some information, but they don’t publicly share it. And it’s snapshots. It’s not a continuous, up-to-date panel. And so years ago, I think it was January 2017, I decided that I was just going to make it myself, which is kind of a crazy thing to do.

I wasn’t teaching that month, I set aside everything else, and I began a months-long process of exhaustively researching every abortion facility in operation in the US since 2009. I used state licensing databases, web scraping, directories, everything I could think of. I’ve cross-checked it over the years with every source I can. I received a grant from the Society of Family Planning to start surveying appointment availability at all the facilities to add to the database as well. I have 30 undergraduate students at Middlebury. And quarterly, we call—they call—every abortion facility in the country to see when the next available appointments are. So I started adding that to the data.

My primary purpose was to use this for academic research on the effects of abortion access. This was data I needed for my models, but I got a call from some geographers at Esri, the software company that makes ArcGIS, and they pitched the idea of using their tools and my data to build an abortion access dashboard. The dashboard provides a resource that anyone can access to explore and understand where abortion facilities are today, what appointment availability looks like, which cities are receiving the highest proportion of people traveling for abortions, and how it’s changed over time. You can also download the data if you want to use it for your own research.

I fervently believe in open science, especially when you’re working in a politically charged area. Folks might say, “Oh, I suspect that Caitlin has some sort of agenda. I can’t trust the things she’s telling me.” Well, for anybody who worries about that, I publish all my data and code online—everything. People can and do use these to replicate all my work and to conduct their own. I need everybody to have the data. Since I can’t write all the papers, I need other people to use my data to write other papers. I just really wanted to disseminate the information to academics. And I wanted policymakers and journalists and anybody else who wanted to be able to really quickly describe the changing landscape of abortion to have a tool they could use to do it.

Hannah: So what does all this data tell you about why distance has such a large effect?

Caitlin: The effects are larger than some people might expect, particularly economists. At first glance, the fact that so many women seeking abortions are stopped by distance might not appear to follow our theories of rational behavior. After all, we know that childbearing has enormous economic implications for a woman and her family. If somebody is pregnant and they really, really, really don’t want to give birth, and they’re comparing the cost of giving birth against the cost of figuring out how to drive 100 miles to get an abortion, it seems obvious that they would just drive.

And that makes a whole lot of sense if you have money or credit. If my kid needed health care in Sweden tomorrow, I would get on a plane and be in Sweden. But the people who are seeking abortions, 75 percent of them are living below 200 percent of the poverty line. They’re low-income. Half of them are poor. Most of them are already parenting. More than half are reporting disruptive life events: They’ve fallen behind on the rent. They’re at risk of being evicted. They’ve just lost their job. They’ve just broken up with a partner. And if you match them to their credit reports, which a group of researchers has done, more than 80 percent are credit constrained. This economic vulnerability isn’t just a side note about their lives: It is a reason many of them are seeking abortions. One of the most frequently cited reasons for abortion is financial. I don’t think it takes too much imagination to realize, oh, traveling 100 miles, that might be really hard for low-income women in difficult circumstances. And that’s what we see in the data: Distance is a substantial barrier.

We saw this in the pre-Dobbs era. Parental involvement laws requiring minors to demonstrate one or both parents are aware of and consent to their abortion resulted in increased teen births, and the farther teens would have to drive to avoid the parental involvement requirement, the more births went up. Mandatory waiting periods also increase birth rates. These laws usually require two trips to a clinic, because they force a woman to wait 24–72 hours to be sure she still wants the procedure. The effects are larger the farther away the destination is. And then you can look at supply-side regulations, which some people call the Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers, or TRAP, laws. These are restrictions that were closing abortion facilities and increasing distances people had to travel to reach facilities. I and other researchers studied these types of shocks that were arising from facility closures to see what happened, and it’s so clear in the data in the decades leading up to Dobbs that distance is a really important dimension of access.

Before this body of research started coming out, around 2017, you’d see judicial rulings where the court would say, “Well, I don’t think 150 miles sounds that far. That seems doable. That’s not too far.” But what we can see in the data is the first 100 miles will stop one in five people who want an abortion from getting one.

Hannah: Let’s return to the period since Dobbs. What have you seen? Do we know how many clinics closed because of Dobbs, for example?

Caitlin: Journalists call me all the time and ask me that, but the number of clinics that close is really not a great measure of the effects of Dobbs. Many of the facilities just stopped providing abortion. They’re still providing other services. Other facilities moved. For instance, one moved from Memphis, Tennessee, to Carbondale, Illinois. Do you want me to count that as a closure? They wouldn’t have moved if it weren’t for the ban, but they are still technically open.

And then even in non-ban states, facilities close and open, and, almost ironically, Dobbs has accelerated expansions of abortion access in states that protect it, places like New York and California. More hospitals started advertising abortion services after Dobbs. There are more telehealth providers. Measured in total, the net change of abortion facilities in the US was only about negative 20. You’d be fair to think, “That’s nothing.” But what that doesn’t show is that there is this dramatic expansion in inequality of access.

Before Dobbs, the average American woman lived 25 miles from the nearest facility. After Dobbs, about a quarter of American women live in ban states and have experienced a reduction in access. In that group, the average affected woman is now about 300 miles away from the nearest facility. So it’s not about the number of facilities. It’s about where the facility is located. And there has been an absolutely huge increase in distance. And I think that’s what tells the story: this expansion in inequality.

Hannah: Thank you so much. To close us out, do you have any other projects that you’re working on right now or priorities you want the policy world to know about?

Caitlin: Yes, I have one, and it comes with a bit of a data lament. Dobbs has sparked a surge in academic interest in studying abortion. And from my perspective, that’s fantastic. I’m contacted all the time now by graduate students and professors who would like to use my data. I give it out to everybody because, again, I’m all about open science. And I’m seeing all of these amazing new projects looking at the ripple effects of abortion access, beyond births—on intimate partner violence, child maltreatment, maternal morbidity and mortality, child morbidity. And I’m working on a project with some collaborators at Stanford and Berkeley. We’re really interested in using Medicaid claims data to look at the effects of abortion policy on maternal health outcomes. The vast majority of people seeking abortions, or at least a large majority, are Medicaid eligible, so it’s a reasonable place to look. We’re working right now on a project that uses pre-Dobbs data, because it just takes a really long time for the government data to be released and updated. So we still don’t have all the available data for the post-Dobbs period.

And here I will make a plea, or impassioned call, for accessible data. Obviously we want to protect people’s privacy and be reasonable. But we need accessible data to let us understand really important public health and economic questions. I understand that there are people acting in good faith on both sides of this issue. What I don’t understand is how anybody wouldn’t want to know the effects of the policy on US families. I just don’t get that.

What’s happening right now, as best we can tell, is the poorest and most vulnerable families, many of whom already have children, are giving birth to children as a result of abortion restrictions. It’s financially destabilizing. This increases the risk of adverse health outcomes. It increases the risk of child maltreatment, intimate partner violence, a whole series of adverse outcomes for fragile families. And I would think, from a policy perspective, we would want to understand the extent to which that’s happening, where it’s happening, and then think about effective policy responses. You know, people might reach different conclusions, but gosh, don’t we want the evidence? Don’t we want to know? We need good data now more than ever.

If you ask Eleanor

“There was a time when a woman married and her property became her husband’s, her earnings were her husband’s and the control of the children was never in her hands.

The battle for the individual rights of women is one of long standing and none of us should countenance anything which undermines it.”

– Eleanor Roosevelt, My Day (August 7, 1941)