The Musical Chairs Theory of Housing

March 25, 2025

By Paul Williams

Fireside Stacks is a weekly newsletter from Roosevelt Forward about progressive politics, policy, and economics. We write on the latest with an eye toward the long game. We’re focused on building a new economy that centers economic security, shared prosperity, and rebalanced power.

For hundreds of years, thousands upon thousands of New Yorkers all moved on the same day. Moving Day, which fell on May 1 each year, coincided with near-universal annual lease renewals from landlords across the five boroughs. Like a tremendous game of musical chairs, families switched places. Perhaps a family with new children moved into a newer, larger home. And a family just starting out, new to the city, moved into a just-vacated unit.

While each round of the children’s game begins with one seat being removed, this would clearly be catastrophic for a housing market. For a booming city that’s attracting new families with good-paying job opportunities and quality public schools, we need to be adding chairs each round. No amount of financial assistance alone can solve that fundamental supply need.

In the New York example, back in the time of Moving Day, this supply problem was taken care of: The biggest apartment building boom in New York’s history was the 1920s. The city sported a healthy vacancy rate of 7.8 percent—enough empty chairs for new and growing households to find something suitable.

But over the course of the 20th century, changes to New York’s planning laws put a damper on the chair-adding. New York’s now-infamous 1961 downzoning put a bottleneck on the number of apartments that could be built in the metropolis. Over the decades, the vacancy rate trended further and further down. Today, it stands at one of its lowest points in the modern era: 1.4 percent.

In the New York housing market today, it feels like a chair is being removed each round, with 10 people all angling for that one empty slot. But it’s not the fastest person who wins; it’s the one with the most money to win bidding wars, a phenomenon that hit housing markets across the country in the years following the pandemic. In some of the most constrained markets, from Brooklyn to Boise, those bidding wars continue to this day, not just with for sale homes but for apartment rentals. Last week, Bloomberg reported that, in Manhattan, “27% of last month’s new leases were signed after bidding wars, a record share.”

Bidding wars don’t just pit well-to-do families against one another—they lock out working-class and even middle-class families from the cities where job opportunities are, and from the cities they already work in. In the much-publicized mass exodus from expensive cities over the past several years, the attention has been on tech and other remote workers “taking over” idyllic places, like mountain towns in Idaho. But the data paints a very different picture. Business Insider last year ran an account of a trades worker who moved from the Bay Area to Bozeman, Montana. His reason? Housing costs.

Of course, for the lowest-income households, we have tools in the social safety net to help with housing costs. But those tools, too, are undersupplied, with long waiting lists. More public funds are absolutely needed, but shortening the line to get into the game doesn’t change the fact that the entire system is strained by the underlying lack of chairs.

The housing voucher program entitles the recipient to contribute a portion of their income toward rent, with the government topping up the rest. If you’re receiving a voucher in one of America’s cities, several things about you are true. First, you’ve been on the waiting list for a voucher for a long time—two and a half years on average, and significantly longer if you’re in one of America’s great metropolises. And second, you are in poverty. To qualify for a voucher, a household must be below 30 percent of the median income, which in many regions means less than $25,000 per year.

When a household receives a voucher, they have 120 days to find a home. So how does this relate to the musical chairs? The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) actually did a study on this—years ago, long before “YIMBY” and “abundance” were common parlance.

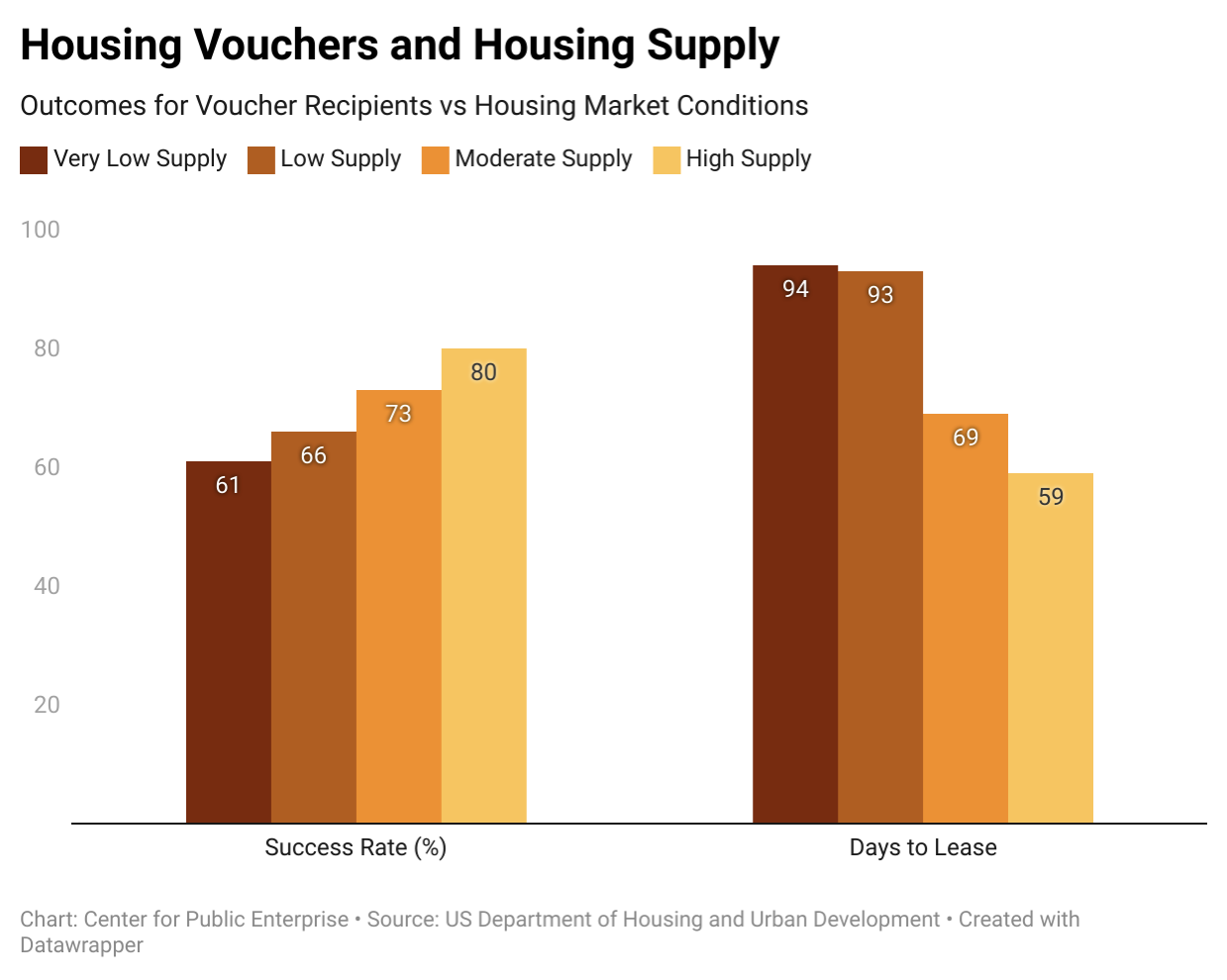

That study found two striking results. First, the rate of success of finding a home to use your voucher on increased by nearly 20 percentage points in markets with plenty of empty chairs as opposed to markets with only a few chairs. Second, in the event that a household was successful at finding a home, the time that it took them to find that home was cut by more than a month (35 days) in highly supplied markets as opposed to very low supply markets.

Once again we find that more chairs are an antidote to these challenges for the social safety net. And the people who know this best are not just the working-class families who rely on vouchers to keep a roof over their head, but our public housing authorities who administer the programs. Public housing authorities know that low-supply markets result in low success rates for voucher recipients, so some will over-allocate vouchers to eligible households on the waiting list, and give those households up to a year to find a home. That is, they give out more than they have funding for because they know with such certainty that there simply are not enough chairs to take everyone, and some of those vouchers will return to them.

This is a smart move by our public housing authorities—it helps them get support out to eligible households more quickly and maximize voucher use—in the same way airlines oversell flights to make sure their chairs don’t go empty, but it also highlights a core challenge for the program and its users: the the housing shortage.

In 30 years, we may look back at this period in American political history as one ultimately defined by housing costs and the challenge of addressing undersupply. I wouldn’t be surprised. We already know what happens in this game of musical chairs—the rich buy the seats, and working- and middle-class people move farther away from their jobs, schools, friends, and family.

But we should be optimistic—the tables are beginning to turn. States like Minnesota have passed ambitious zoning reforms intended to add more chairs to the game by allowing duplexes and quadruplexes on most lots in Minneapolis. States like California have passed laws to allow higher densities in the vicinity of public transit stations, like rail and bus stops. Places like Montgomery County, Maryland, have created new programs under the public housing authority to finance huge new construction projects that have struggled to attract private financing. None of these on their own are enough, but they are all needed.

And 30 years from now, we’ll look back and be glad we made room for everyone.

If you ask Eleanor

“In Detroit, as in every other large city, the housing situation is critical . . . It seems essential that building be undertaken on a very large scale, both by public authority and private enterprise.”

– Eleanor Roosevelt, My Day (November 20, 1945)